„Nothing else remains for you who enter, only hope!”

The view of the mine in Recsk where prisoners were forced to do heavy physical work with basic tools 10-12 hours a day in every season. The camp in Recsk „opened its gates” on the dawn of July 19, 1950. 1500 prisoners who were hauled here without a court decision were forced to work under minimal conditions of existence continuously in the stone mine in the camp created following the example of Soviet Gulag camps. As time passed and as the number of people in the camp increased the guards became more and more violent. They inhumanly chastised, tortured and starved the prisoners. The place already had five barracks by late autumn 1950. The camp had 1300-1700 prisoners at its height. When closing the mine in 1953 all prisoners released were forced to sign a confidentiality document confirming they would not tell anyone about the conditions in the camp.

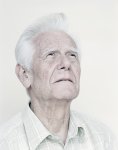

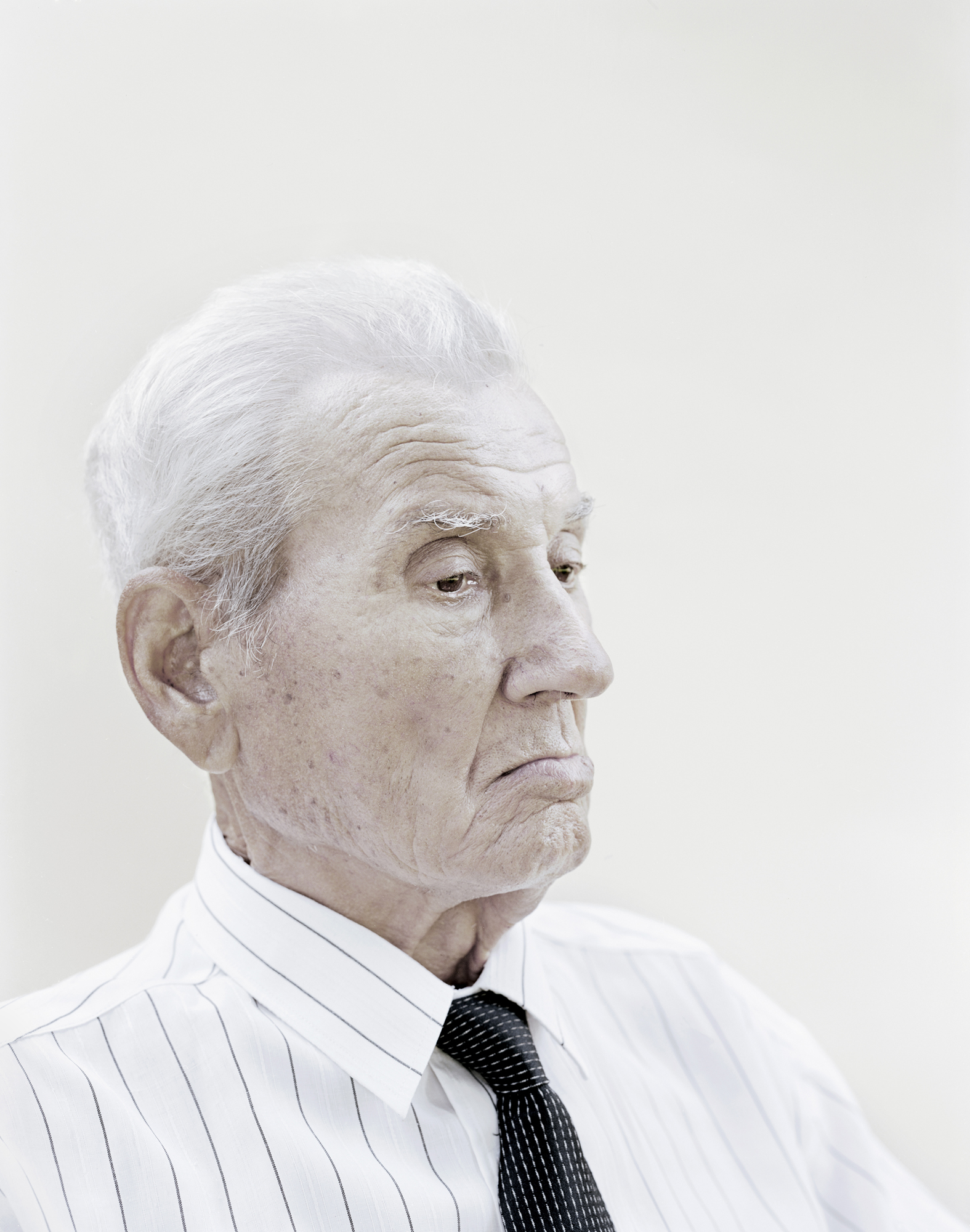

Portrait of Ervin Ernst

Ervin was sentenced to 11 years of forced labor during a show trial in 1954. He was charged with organizing the overthrow of the people's democratic state. Ervin was only at the beginning of his 20s at this time. He spent 2 years in prison in pit no. 9 in Csolnok mine. He was released in 1956.

Quote from Ervin: “One has periods in his life where everything blurs, one day cannot be distinguished from another. In my view this is the essence of being in prison: you live by merely existing... At the same time there are days, events or maybe moments which get carved in your memory for good and appear as real and fresh even decades after.”

A dark cell carved into a rock on floor -3 in the fortress prison of Veszprém, Hungary. Mostly church persons were imprisoned here. Convicts were given only a sack stuffed with hay to use as a pillow.

A Böhring drill of the period which the prisoners used in the mine in Csolnok, Hungary.

Portrait of Ferenc Balogh

Ferenc was a 23-year-old university student when he was arrested in 1951. He was going to get married to his fiancée in 10 days’ time. He was charged with organizing Catholic youth camps. He was imprisoned in the Internment Camp in Kistarcsa, and for a long while his parents knew very little about where their son could be. He was released in 1953 when Prime Minister Imre Nagy ordered the closure of all internment and labor camps. After his liberation he married his fiancée who was then expelled from university for this reason.

Quote from Ferenc: “I was arrested by the people of the State Protection Authority at 2 am on May 11, 1951. I can never forget this. I was being interrogated for three months, day and night. Then they made me sign an internment decision. I did not want to sign it at first but I saw they would come and beat my head. They hit my head against the wall and kicked in me. I had to lie on the bed in the cell motionless because if I had moved I would have had to stand up and hold a sharpened pencil with my forehead against the wall.”

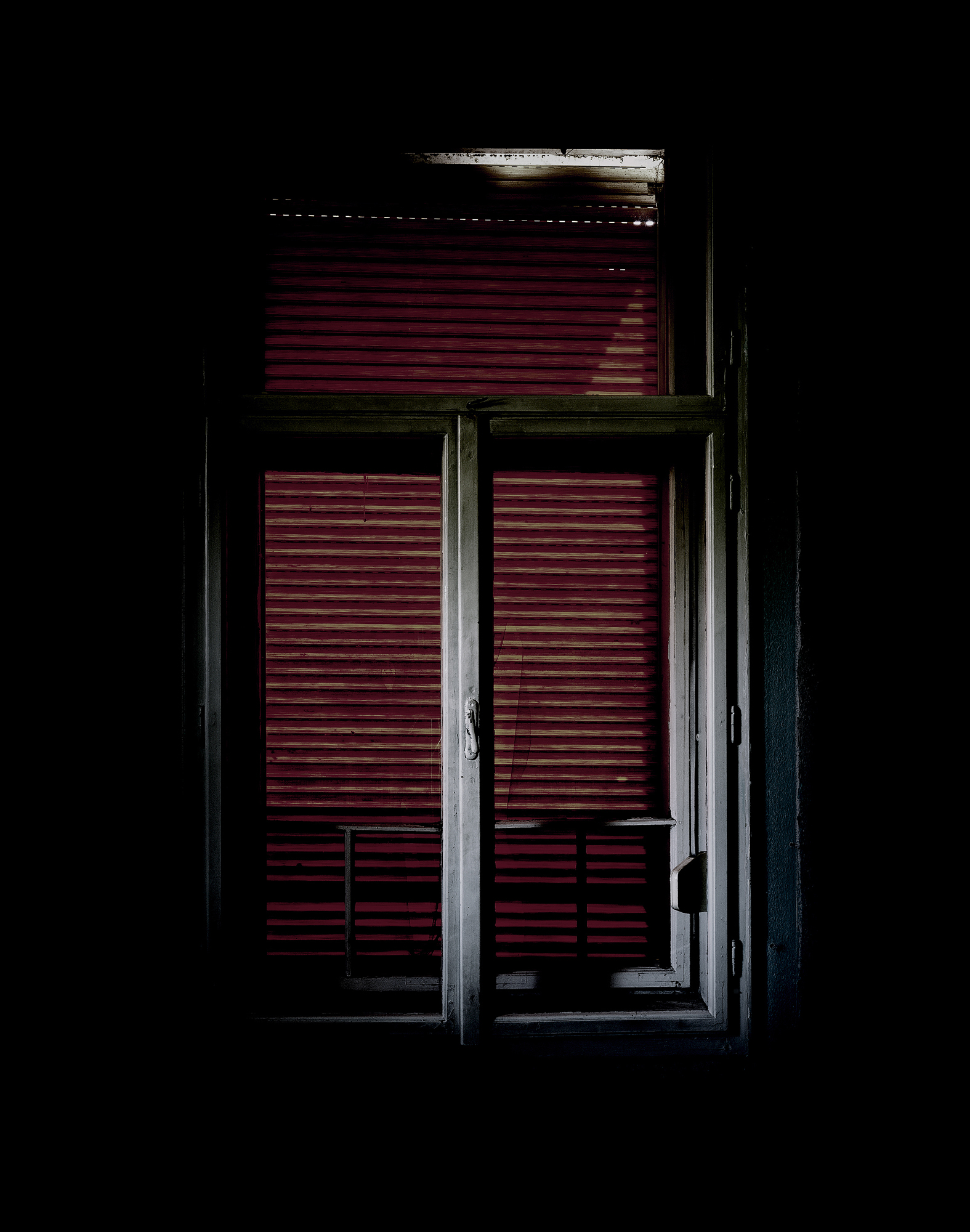

Detail of Internment Camp in Kistarcsa, Hungary.

(1949-1953)

In spring 1949 the internees in Buda-dél internment camp were moved to Kistarcsa and this camp became the Central Internment and Concentration Camp. On 5 May, 1950 the State Security Authorities occupied the camp. All the windows were white-washed and ‘free’ movement inside the camp was prohibited. The number of people in the five male and one female ‘regiment’ was around 2-3,000 in Kistarcsa. There were no beds and the prisoners had to sleep on mattresses and blankets on the floor with a space of about 50-60 cms for one person. An old and shabby prison building stood next to the building of the Headquarters of the Commander.

Toilet bowl in one of the cells of Kisfogház. It was a frequent method of tormenting prisoners to feed them with salt and make them drink from the toilet.

Portrait of Sándor József Rácz

József wanted to become a physician and he studied at Medical University at the time of the 1956 revolution. He would have liked to become a surgeon. He was active in the organization of the revolutionary movements of 1956. He was only 22 years old at the time. He was arrested on February 1, 1957 after having been reported to the police. Judge Vilmos Szegedi asked for death penalty for him at first instance, whereas Judge Gusztáv Tutsek gave him life sentence. He stayed at the most dreadful prisons. Eventually he was freed at the time of the 1963 amnesty. A few months after the portrait was taken József passed away due to a long-standing illness.

Detail of mine in Recsk, Hungary.

Piece of a prisoner’s shoe in Recsk, Hungary.

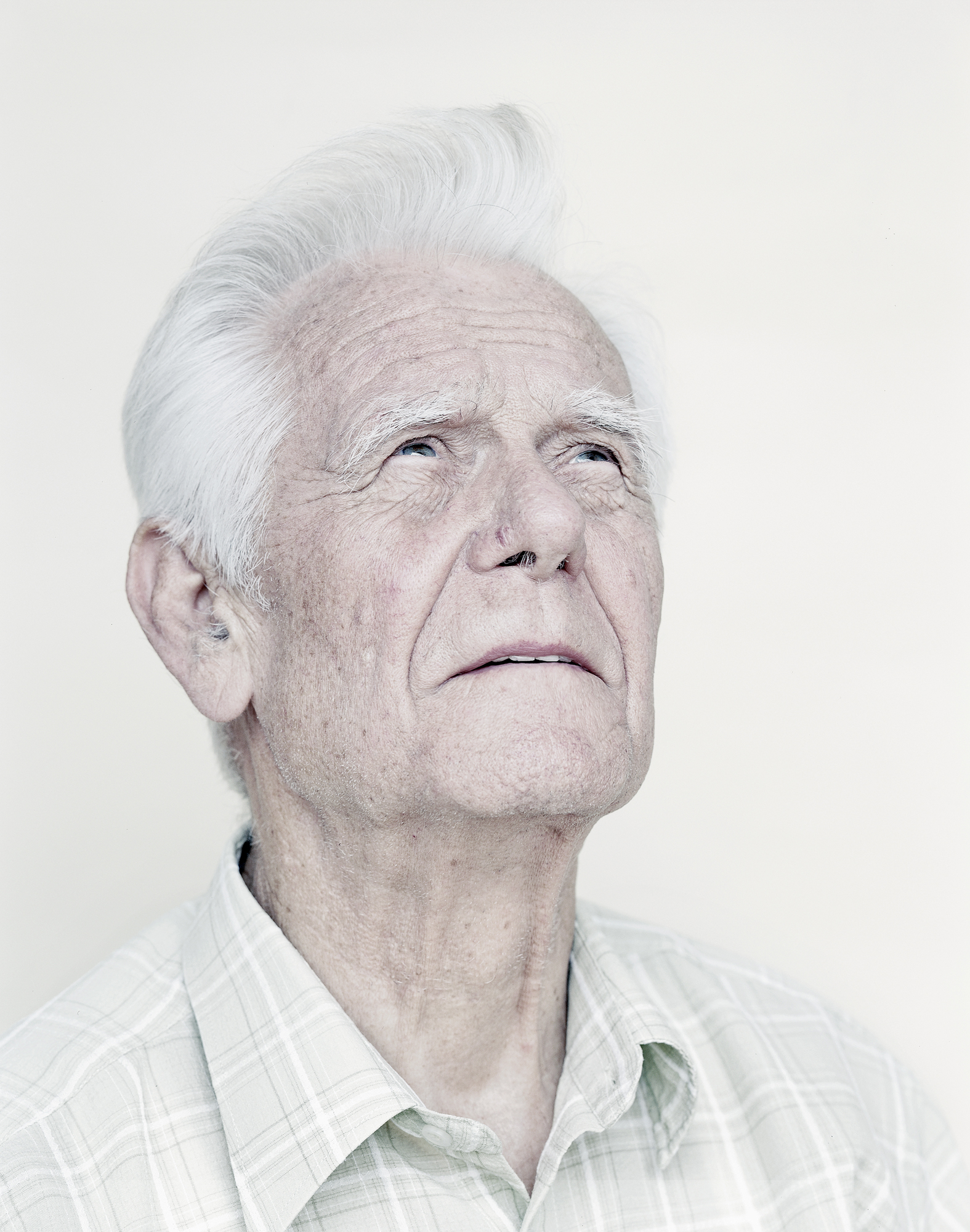

Portrait of István Válóczy

István was merely 23 years old when he was summoned as a witness to a firefight in November 1956. He was interrogated and then, based on his own confession, he was arrested. The charges were organizing and leading the firefight. The court decision was life sentence, deprivation of all possessions, and 10 years of deprivation of political rights. Eventually he received amnesty after 5 years and 3 months, in 1963. He had just lost his mother while he was spending his years of imprisonment in the Central Collecting Prison, but he only learned it later from the guards. His wife also divorced him during the time of imprisonment when their common child was only 2 and a half years old.

Quote from István: “It was not allowed to look up during the walking hour in the prison but when it was raining or snowing we could see the sky reflected from the puddles. We were allowed to walk only with our heads bent down and hands at the back. When you come out of the prison you notice that the world is colorful. There are colors. Inside everything is grey. The days are grey. The walls are grey. The clothes of the guards are grey, everything is grey. The hopeless time spent in prison is grey. There is only one color: grey. Outside everything is colorful. The world is colorful, the flowers are colorful. The sky is blue.”

The inner facade of the Budapest Metropolitan Prison Service in Markó Street.

After 1945 the prison in Markó Street became the center of the jurisdiction of the people’s democracy. This is where they had trials and pronounced death sentences for war crimes and crimes against the people which were carried out in the courtyard of the prison. This is, for example, where Ferenc Szálasi and Béla Imrédy, former prime ministers were executed. The prison was so filled up by 1946 that 1800-2000 prisoners were crowded in a building originally built for 700 people. They kept 30-35 prisoners in a cell that was built for 6-7 people. The cells were full of lice and bedbugs which were impossible to eradicate under these conditions.

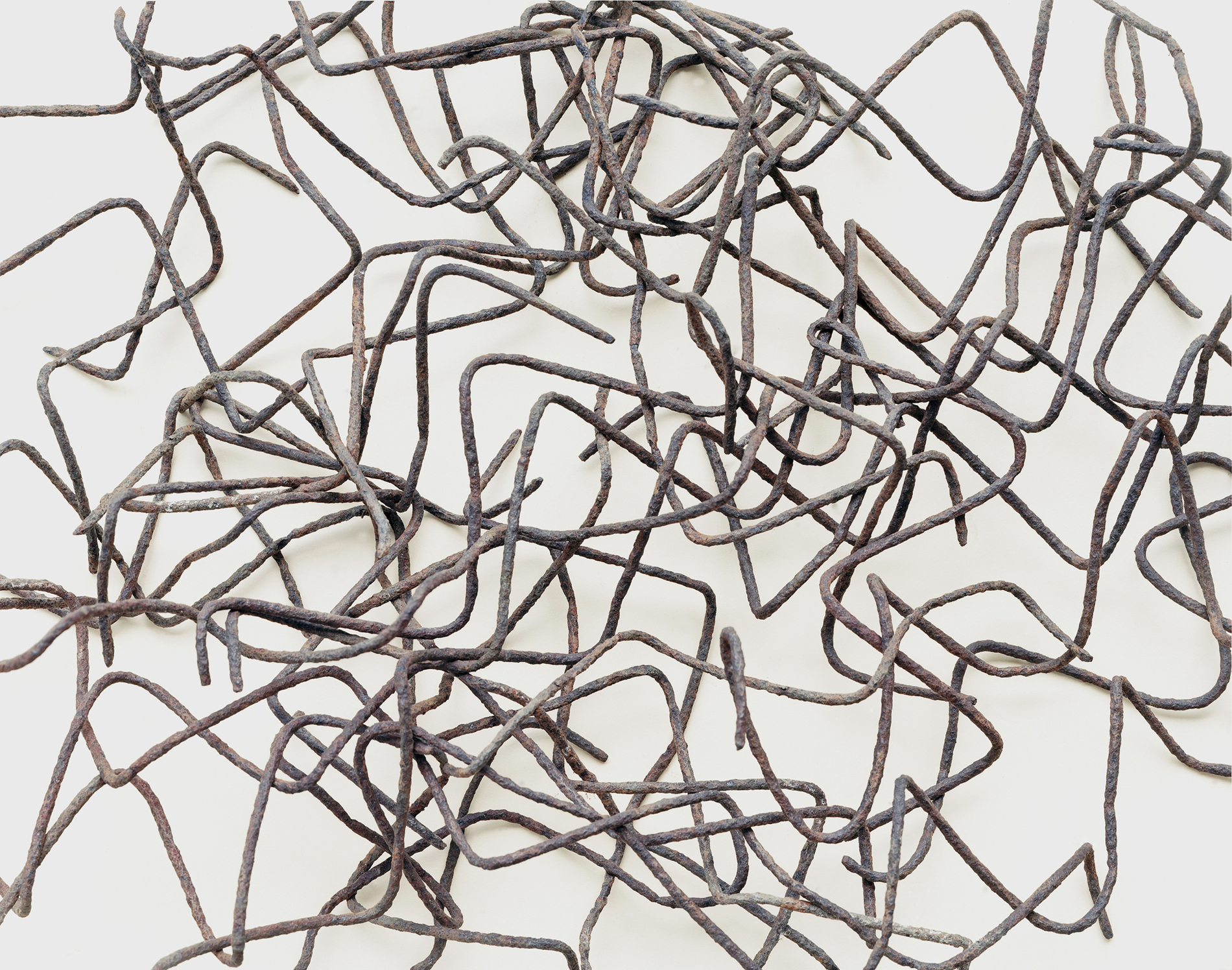

Pieces of the fence of the prisoners’ camp in Csolnok, Hungary.

The interior of a cell from the penalty unit of the Prison in Vác, Doberdó.

A windowless standing cell is one of the most appalling places in Doberdo, the prison in Vác, in which the locked-up prisoner could do nothing but stand. Squatting, sitting down on the floor or relaxing the body in any way was impossible. In case the prisoner got sick, fainted or could not take up the posture for the normalization of blood circulation – even if the person survived the time spent in the cell – they would suffer from an irreversible impairment due to the lack of blood circulation in the brain. As the prisoners recollect, almost all captives of Doberdo tried to commit suicide in one way or another after three days in the hope of avoiding their further suffering.

Portrait of János Straub

János was in prison for 16 years and 2 months. This included 180 days of rigorous surveillance and 180 days spent in a dark cell. He was 21 years old then.

He was given this sentence in a show trial in 1958 on the charges of attempting to cross the border illegally, taking part in the revolution, and multiple attempts of murder. He was released in 1971.

Peephole on a cell door in the cellar prison of the Hadik military base. Guards were watching the convicts through this to prevent rebellions.

The former Hadik Barrack became the headquarters of the Military Political Department of the Ministry of Defense in 1945.

They created prisoners’ cells in the basement where political prisoners were kept under inhumane conditions.

Shower room.

Prisoners had only one minute per week to wash themselves.

View of Badacsony and the former workers’ mine.

The prisoners’ camp in Badacsonytördemic operated from about 1949 to 1954. Few documents have remained from the prisoners’ camp since they strived for removing all the traces. The basalt cobbles which they used for constructing the roads of Budapest in the Rákosi era were mined in this camp for many years. It can be seen from the silhouette of the hill which parts were illegally mined. The mine was closed in 1960 and then the area was declared a national natural reserve.

Portrait of Ottó Koós Békei.

Quote from Ottó: “We fell into captivity on October 2, 1944 near Uzhghorod because we were surrounded by Russians. We were forced to march from Uzhghorod to Stari Sambor. There we were put on wagons on December 6, 1944. After 21 days in the wagon we arrived in Ufalei, Tchelyabinsk territory in the Ural Mountains. As we later learned from the Russians 650 people died on the way. I also caught the typhus with rash and lost weight, I was 48 kgs. After staying in different camps, the Soviet military court gave me death sentence on December 30, 1950. However, death sentence was no longer a valid penalty method so I was sentenced to spend 25 years in an penitentiary labor camp. My mother and grandmother were also taken to a forced labor camp and were shot on the way. We could occasionally exchange letters with my fiancée – we still hold the letters we wrote to each other those days.”

Ottó could return home only in November 1955. Even then he was not released. He stayed in the prison of Jászberény and the Collection Center in Budapest. Finally he was freed on October 8, 1956.

The place of the lower camp in Recsk today. It can be found on the left side of the way to Sirok, east of Recsk. There were 160-170 prisoners working here.

A stone from the mine in Recsk.

Portrait of Lajos Kovács

Lajos was arrested with the charges of holding and hiding guns during the 1956 revolution. Due to his young age (14 years old) instead of a prison he was taken to the Szőlő utca re-education institution for 6 months. The absurdity of his story is that the son of the policeman that beat him at his interrogation, being the local mayor, gave him an award for his participation in the 1956 revolution.

Internment camp in Kistarcsa

(1949-1953)

In spring 1949 the internees in Buda-dél internment camp were moved to Kistarcsa and this camp became the Central Internment and Concentration Camp. On 5 May, 1950 the State Security Authorities occupied the camp. All the windows were white-washed and ‘free’ movement inside the camp was prohibited. The number of people in the five male and one female ‘regiment’ was around 2-3,000 in Kistarcsa. There were no beds and the prisoners had to sleep on mattresses and blankets on the floor with a space of about 50-60 cms for one person. An old and shabby prison building stood next to the building of the Headquarters of the Commander.

Penalty unit in Szeged Csillag Prison

The victims of the show trials conducted from 1945 to 1956 and the victims of the retaliation following the 1956 revolution were spent their years of captivity in this prison. This was also the place where Mátyás Rákosi was imprisoned during the 1930s. The Communist leader who first was sentenced to 8 and a half years, and then received a life sentence enjoyed exceptionally good treatment in Csillag. His cell was open the whole day, he was allowed to walk freely between his clerk office and cell. He had a lot of money, and he was in regular contact with his Moscow relatives through his lawyer.

The hexagonal interrogation room in the tower of the Rajk villa.

The infamous Rajk villa on Svábhegy where László Rajk Sr. and his “fellows in crime” were interrogated for weeks. There was a night bar with lanterns next to the villa where music was playing continuously so that the howls coming from the basement could not be heard.

Portrait of László Rajk. ( 1949 - 2019 )

Hungarian Kossuth prize-winning architect, scenic designer, one of the former members of the democratic opposition, politician. His father was László Rajk, Minister of Interior who was executed in October 1949 after a show trial, before his son was one year old. Rajk was separated from his mother, Julianna Földi who could get her son back only in 1954, after she was released from prison.

Quote from László Rajk, on his father: “My father was one of those who created the Rákosi regime, which later grew into the Kádár regime. I am actually proud to have taken part in destroying this regime.”

The scene of the Rajk-Brankov show trial in Vasas Headquarters in Magdolna Street. This is where the bench stood.

László Rajk was Minister of Interior in Rákosi’s government from March 1946, and Minister of Foreign Affairs from August 1948. He actively participated in designing the internment processes and forging the results of the illegal “blue-ballot” election. Rákosi arrested Rajk on Stalin’s advice at the beginning of June, 1949. Rajk was sentenced to death during a show trial and was executed on October 15 on the charges of espionage and organization against the state. He was rehabilitated in 1956.

Beloiannisz Telecommunications Factory (BHG) phone from the 1950s. One of the most important clients of the factory was the Ministry of Interior. The State Protection Authority used this model too.

Portrait of György Marosán Jr. (Born: Budapest, March 11, 1946)

Physicist, son of György Marosán Sr., communist politician. As the ideologist of the violent application of the dictatorship of the proletariat, György Marosán Sr. gained fame for, among other things, that at the time of the 1956 revolution he demanded that, even if by shooting into the crowds (“From today on we will shoot”), they maintain the communist dictatorship. This is how he became the face of the retaliatory state power. He was also sentenced to death in 1950, at the height of Rákosi’s terror, however, his sentence was modified to life sentence at second instant. Finally, he was released from prison after 6 years and then immediately offered his services to the leadership of the party.

Quote from György Marosán Jr., on his father: “As time passes I love him more and I am more and more critical of the regime that he created.”

Detail of Rákosi’s villa in Szabó József Street.

The dictator Mátyás Rákosi and his wife lived here until 1949, and then they moved to Szabadság Hill for security reasons. They kept the villa for themselves and also pretended to be still living there.

Portrait of András Szirtes. (Born: Budapest, July 6, 1951)

Bela Balazs-prize winning film director and camera operator, editor, actor and musician. His father, Zoltán Szirtes worked in the Commercial Department of the State Protection Authority as a captain. However, in 1951 he was sentenced to two years of prison in a show trial, one year of which he spent in a private cell. The charge was espionage for Yugoslavia.

Quote from András Szirtes, on his father: “My father, as soon as he entered the office, was stripped naked, got spat on, kicked, beaten up. When he fainted of the pain he was poured water on and beaten up again. He shat himself out of pain. Then he was beaten up again. This went on for hours and hours when finally he was pushed into a dark cell. He was 31 years old then … (Excerpt from his family novel, “Vándorszem”, (“Wondering Eyes”)

The bench of the judge in the court room of show trials, Fő street, Budapest.

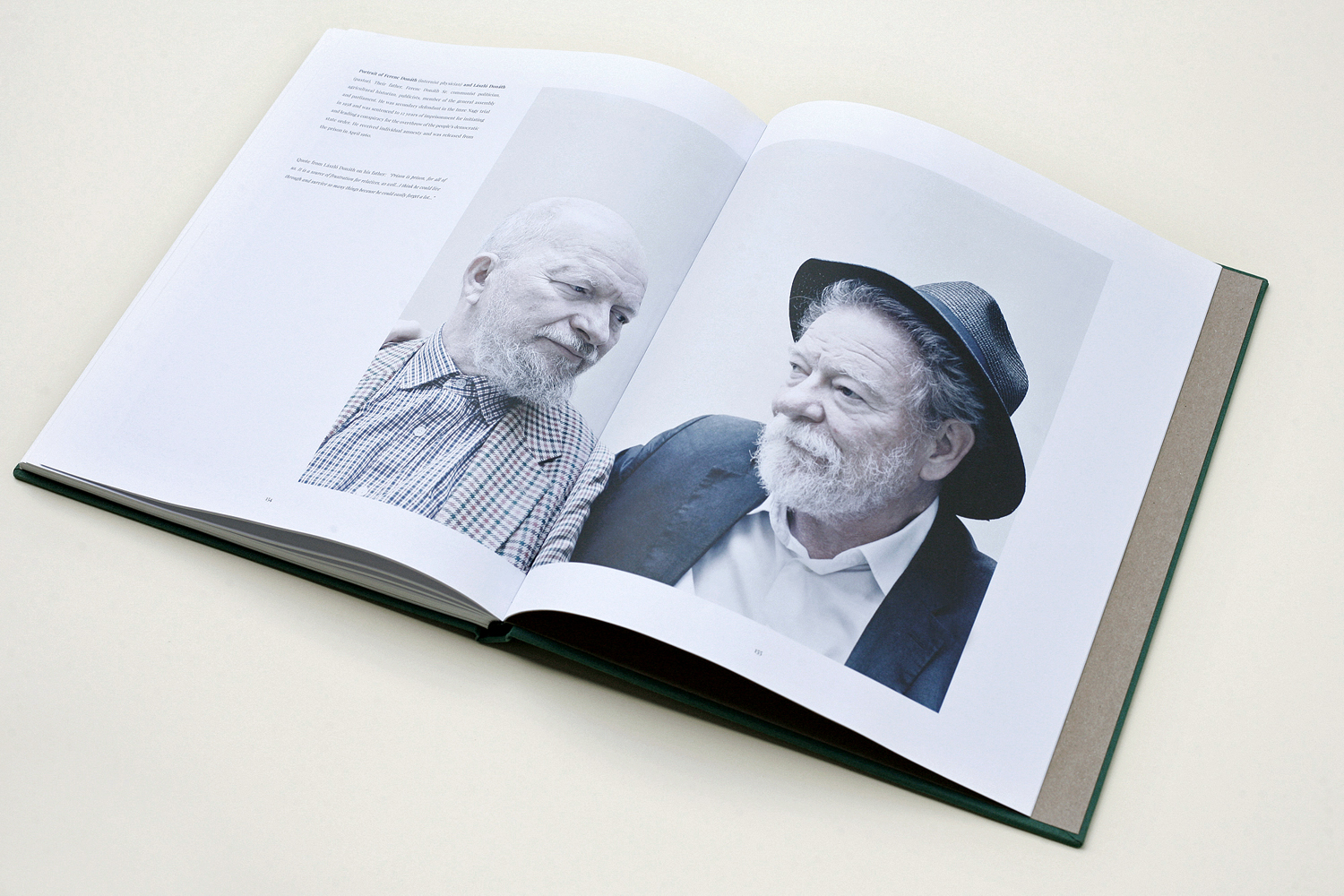

Portrait of Ferenc Donáth (internist physician - left) and László Donáth (pastor-right).

Their father, Ferenc Donáth Sr. communist politician, agricultural historian, publicists, member of the general assembly and parliament. He was secondary defendant in the Imre Nagy trial in 1958 and was sentenced to 12 years of imprisonment for initiating and leading a conspiracy for the overthrow of the people’s democratic state order. He received individual amnesty and was released from the prison in April 1960.

Ferenc Donáth in the dock. (Source: Fortepan, Frames from the recording taken at the trial. The film recordings were classified at the time and they became accessible for the public only in 2008.)

Gallows in the Small Prison.

After repressing the revolution in 1956 the people’s courts sentenced about 26000 people to shorter and longer periods of imprisonment or death from November 1956 to 1963. Death sentences were usually carried out in the courtyard of the Small Prison. This is where Imre Nagy and his associates were executed on the dawn of June 16, 1958.

The denture that was excavated when the martyrs of the Imre Nagy trial were exhumated which finally helped identify Imre Nagy’s mortal remains. (Owned by Katalin Jánosi)

Prison door of the time from Csillag Prison, Szeged., Hungary.

Portrait of János Révai. Son of József Révai. Physicist. (Born: Moscow, May 14, 1940)

József Révai. Born: József Léderer. (born: Budapest, October 12, 1898, Died: Balatonaliga, August 4, 1959) Communist politician, writer, the important determinant of cultural policy and the leading ideologist of the party at the time, a member of the omnipotent “Quartet”. He was the omnipotent controller of cultural life in Hungary from 1948 to 1953. He worked out the principles of socialist realism, the declaration and merciless enforcement of its primacy, as well as the nationalization of schools in 1948.

“…Noone knew the truth more than József Révai. They knew what was happening in the Soviet Union, that innocent hundreds of thousands of people perished in the Gulag just as in Auschwitz, and that the trials were show trials. What kind of faith was that to which they stuck literally through thick and thin…”

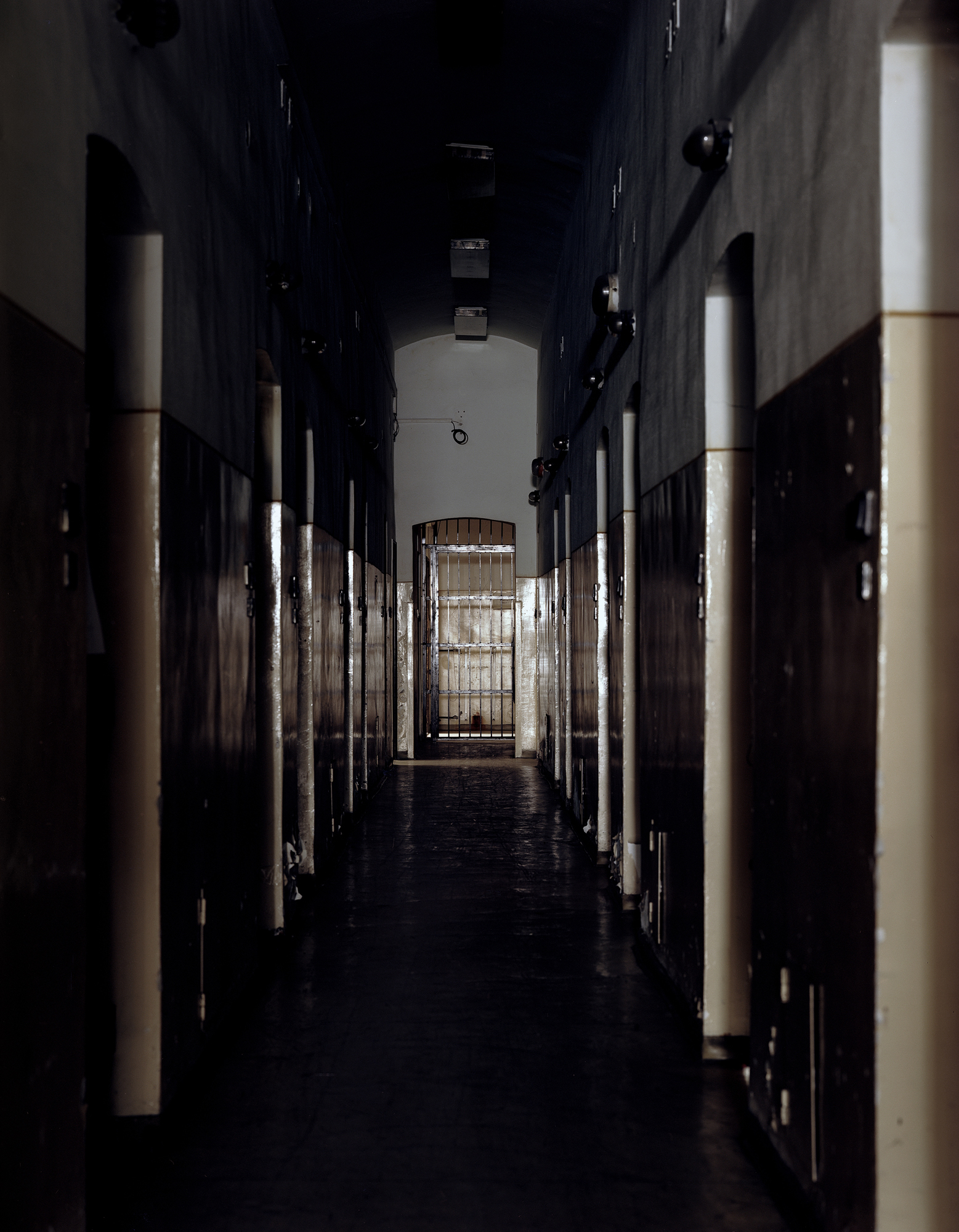

One of the most terrifying prison from the 40's. Budapest, Hungary.

Many political prisoners were tortured and executed here during Matyas Rakosi's dictatorship.

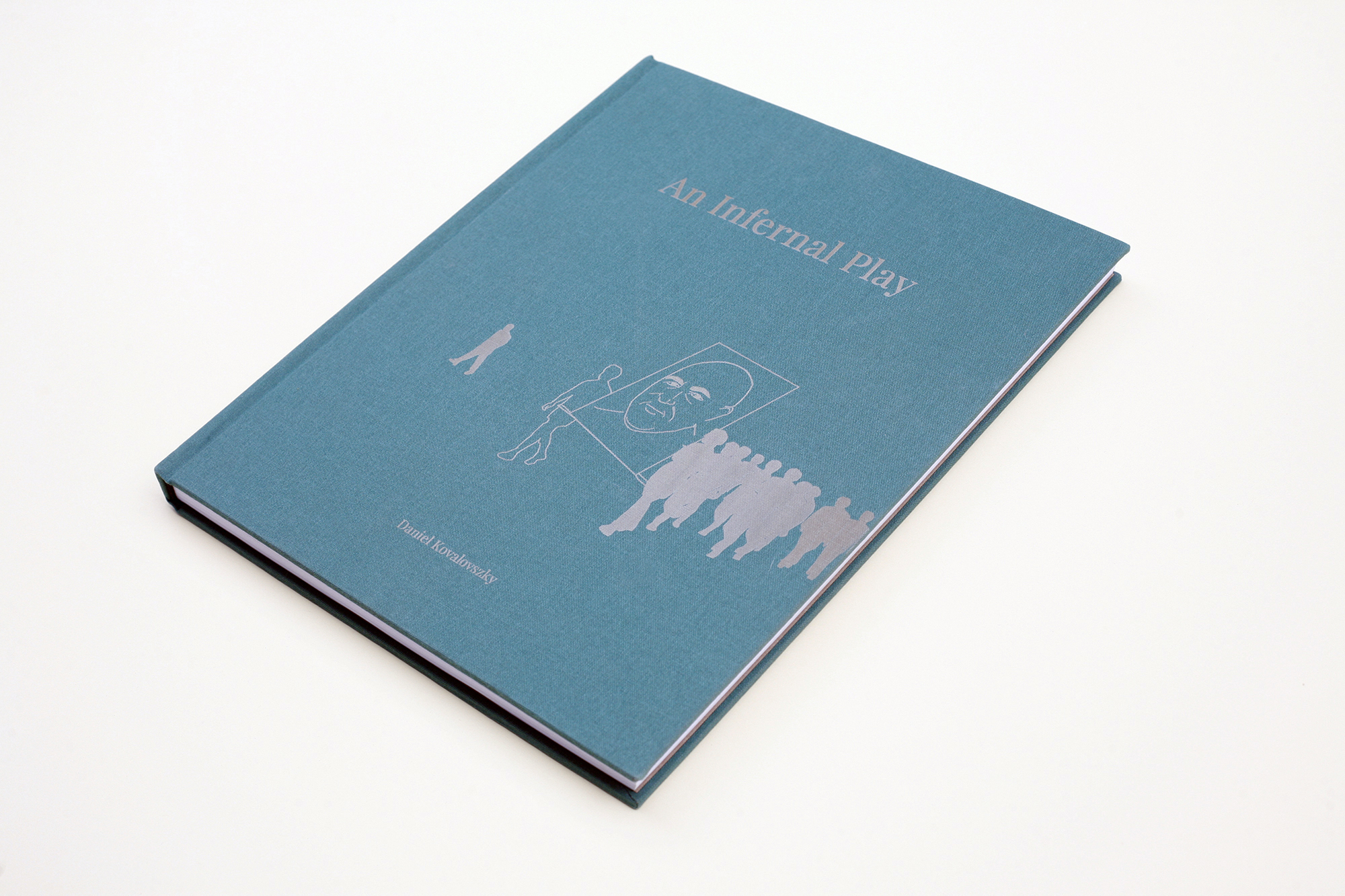

Scenes of an Infernal Play 2016 - 2021 ( A selection of photographs from the work )

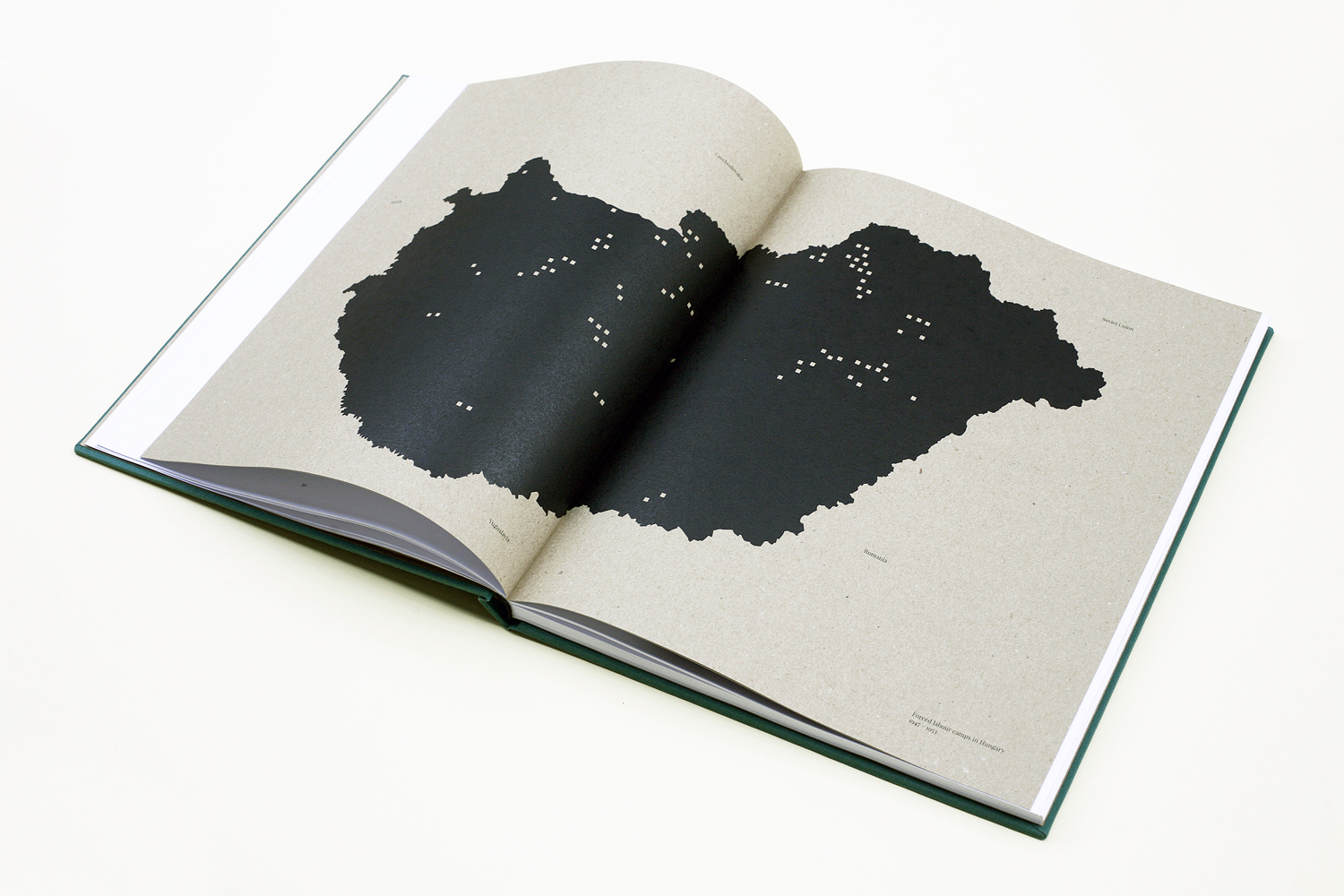

In 1945 in Hungary, Mátyás Rákosi the leader of the Hungarian Communist Party, following the Soviet example, introduced a new Stalinist dictatorship in which human rights were severely violated. He established the State Protection Security (AVH) which was the secret police of Hungary from 1945 until 1956. It was responsible for much cruelty, brutality and many political purges. As a result of show trials, several hundred thousands of political convicts were sent to forced labor camps, were imprisoned and hundreds were executed based on fictional charges. In most cases the charges consisted in supplying data to western powers and secretly organizing a revolt against the people’s power.

Having found the memoirs of the political prisoners a very dreadful and unknown world opened up for me and made me realize how little and superficial my knowledge is about this historical era. I started reading it and a deep and a dark world opened up for me which grabbed my attention instantly and made me realize how little and superficial my knowledge is about this period of the Hungarian history. The more I read about the world of prisons the more I connected it to a visual symbol system which I wanted to bring to life through the photography. I decided to start a visual collection to shed light on a segment of what was happening during these obscure years that is unknown to many but still significant: the world of prisons in Hungary between 1945 and 1963. I have identified the timeline to be examined from the opening of the first labor camps (1945) to the amnesty (1963). This world is disappearing unnoticed, and with its last old surviving witnesses and the historically important scenes.

The first chapter called Black Hole is about these scenes and the old survivors who have been to the darkest prisons, labor camps of the dictatorship. There is a time pressure for my work as there are fewer and fewer former prisoners who are still alive. They live privately, hidden from publicity, carrying this heavy historical burden for which they no time left in their lives to process and still haven't received proper moral or financial compensation for their sufferings. I have made long interviews with them which have significantly changed my personal approach to the 20th century history of Hungary. The places themselves also continuously disappear or change their function but they will be holding the remembrance of the physical and mental suffering of thousands for a long time. The years survived there cannot be fully represented by photographs, yet I will try to bring forward some of the memories of the prisoners evoking the characteristics of the era.

The second chapter called The Heritage is about the children whose parents were important figures of the Matyas Rakosi's dictatorship but somehow they became the enemies of it from one day to another. Similarly to those mentioned before, they had to face tortures, interrogations, show trials, imprisonment, and in some cases, executions. There were some cases, however, when it was possible to find their way back from the prison to the party leadership. Regardless the fact that we view this as an already processed period of the past, Hungarian society still carries and passes on the burdens and negative reflexes of the past unconsciously. Facing the past as it was never happened. The most important reason for this is that there wasn't social support for naming and calling to account those who committed these crimes so most of them died peacefully in the 80s and the 90s.

My grandmother often told me a frightening story when I was a child, the gravity of which I only came to understand as an adult. When she was a young woman, during the years of dictatorship, my grandfather narrowly escaped getting lost in the maze of the criminal justice system, since an officer of the State Protection Authority started courting my grandmother; my grandfather became an obstacle. The officer made an offer to my grandmother, that should she choose, he could get rid of my grandfather so that no one would ever find him. If that were to happen, I might not have been able to start my work, either.